Social distancing has been adopted worldwide to combat the Coronavirus. Are the returns to social distancing the same in India as in other, higher-income countries? Is the dilemma of balancing lives and livelihoods for India the same as that for richer nations? Going forward, should India be chalking out a more distinctive, data-driven, urgent roadmap for recovery built on its social realities and on what we are learning about the virus?

In this webinar, NCAER hosted Shitij Kapur, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne, Peter Robertson, Professor of Economics and Dean of the Business School at the University of Western Australia, Mushfiq Mobarak, Professor of Economics at Yale University, and Neelkanth Mishra, India Chief Economist and Managing Director at Credit Suisse, to answer these questions. They discussed options for what a distinctly Indian roadmap for recovery could be. Shekhar Shah, NCAER’s Director General, moderated the discussion, during which the panellists also responded to write-in questions from webinar participants.

In this webinar, NCAER hosted Shitij Kapur, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne, Peter Robertson, Professor of Economics and Dean of the Business School at the University of Western Australia, Mushfiq Mobarak, Professor of Economics at Yale University, and Neelkanth Mishra, India Chief Economist and Managing Director at Credit Suisse, to answer these questions. They discussed options for what a distinctly Indian roadmap for recovery could be. Shekhar Shah, NCAER’s Director General, moderated the discussion, during which the panellists also responded to write-in questions from webinar participants.

Shitij Kapur presented results from the independent report Roadmap to Recovery, for which he led an expert taskforce of nearly 100 researchers from eight Australian universities, including in epidemiology, economics, modelling, infectious diseases, public health, psychology, political science, and communications to propose two, evidence-based, actionable options for Australia’s urgent recovery from its pandemic shutdown. The two strategies, an elimination strategy and a controlled adaptation strategy, form the core of this independent report released April-end and produced in just three weeks. Kapur noted that the federal and provincial Australian governments have more or less followed a hybrid of both strategies.

Kapur attributed Australia’s success in suppressing the virus (there were two new reported cases on May 22nd) to its obvious geographical advantage and well-resourced public health and fiscal capacities, but also drew attention to the remarkable and sometimes unexpected cooperation between politicians and experts and the surprising trust between communities and politicians. Kapur emphasised the power of independent inquiry, public trust and transparency and clarity of communications as requirements for success.

Robertson talked about the taskforce’s difficult job of valuing lives vs the cost of the lockdown and explained how they went about it using the “value of a statistical life” for Australia and the lockdown cost the government provided them of about 1% of GDP per month. He talked about some of the regional differences between Western Australia and the rest of the country. He also emphasized the need for effective communication, noting the manner in which various States had come up with clear stage by stage recovery plans.

Mushfiq Mobarak discussed work he has recently co-authored at Yale on whether the benefits of social distancing vary across high- and low-income countries (Barnett-Howell & Mobarak, 2020). Their conclusion was that developing countries may not be best suited for strict social distancing. The benefits may be lower. Developing countries have predominantly younger populations: some 17% of the population in high-income countries was elderly vs only 3% in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); and flattening the curve is unlikely to release the pressure on health systems in LMICs. And the costs of strict social distancing may be higher, because of losses and food insecurity for day-wage workers, migrants, agricultural workers, and micro and small businesses.

This did not mean that there should be no distancing, or that strict social distancing might not have been appropriate, initial emergency response. He suggested a few principles here: enforce universal mask wearing, allow people out only for economic livelihood activities, enlist families to protect the young and vulnerable, ban social and religious gatherings, and wash hands, using frugal innovations such as the “Veronica Bucket” where necessary. Mobarak emphasised the importance of getting money in the hands of the poor: if people are going hungry, they will not obey any social distancing norm. He cited India’s advantage with its Aadhar and Jan Dhan infrastructure that can allow money to get to the poor quickly.

Mobarak ended by reminding the webinar, first, about the need to focus policy attention on gender and specific community issues, and second, on the how data from conventional and unconventional sources could be used to guide policy. He gave the example of big data from cell phone usage in Bangladesh—the poor use cell phones differently from the well-to-do—to target relief payments.

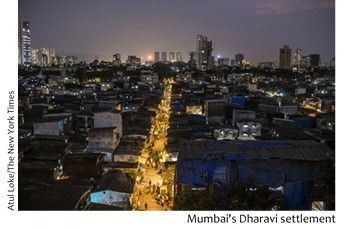

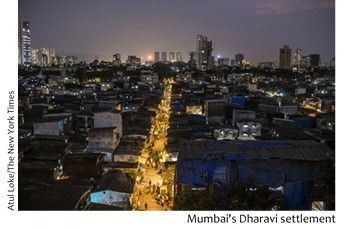

Neelkanth Mishra spoke from Mumbai, India’s most severe COVID-19 hotspot (more than 25% of India’s COVID-19 deaths as of May 22nd). He emphasised that in calculating the economic loss from social distancing, the need for firms to survive—since that is where future economic growth will come from—also has to be factored in. Mishra also mentioned the uncertain ability of local administrations to implement lockdowns in many settings. For example, the Mumbai police’s ability to enforce lockdowns has been severely curtailed both because nearly 1,700 Mumbai police had tested positive as of May 22nd and 18 had lost their lives, and because of the difficulty of enforcing citizen behaviour over long periods of time.

At the same time, with Mumbai’s medical infrastructure under severe stress, there are now very difficult questions about when and how to lift the lockdown. He noted that this was not only the problem with India’s financial capital, but domestic migrants desperate to return homes were also showing the limits of social distancing: One in four migrants returning to Bihar from Delhi on special trains, and one in eight from Mumbai, had tested positive; in addition there were migrants who are making their way home without any assistance.

He noted that the one nation one ration card will be an important step in deploying India’s PDS system to provide food security. In ending, Neelkanth felt that there has to be a greater role for society and not just the state in managing the pandemic. He spoke of panchayats and local councils needing to be much more involved in testing and isolation. He said this would not be easy because of the fear that now prevails in society, so that lifting lockdowns will not be a matter of simply switching things on.

The panellists then had a spirited discussion about the core choices India faced. There was consensus about the need to set expectations right, and the question was how best to do it. Because this had started in high-income countries, the response has been to flatten the curve and to raise expectations of cases coming down in a short time during which the healthcare capacity could be enhanced. This worked in countries like South Korea and Australia, but as is becoming clear, this is proving to be difficult to do elsewhere, so the need is to change expectations and turn efforts to managing the disease rather than trying to eliminate it. This requires a change in mind-set among policymakers, and then among citizens.

India is heading that way, but has a lot of ground to cover to overcome fear and change behaviour. There was consensus that an independently developed roadmap that is distinctly Indian, and that comes up quickly with not just one but perhaps two viable options, would be extremely useful even at this stage, especially if it is well communicated. Not that policymakers need necessarily follow it, but the roadmap could provide the guardrails and the guidelines to inform the discussion leading to action.

This NCAER webinar was attended by over 160 participants. The panellists’ presentations and the video of the webinar are available on this page.

In this webinar, NCAER hosted Shitij Kapur, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne,

In this webinar, NCAER hosted Shitij Kapur, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences at the University of Melbourne,