Shifting Focus: Beyond High-Profile Cases, A Broader Crisis of Abuse

03 Oct 2024

Opinion: Jyoti Thakur.

The recent rape and murder of a young doctor in Kolkata has once again ignited national outrage, as protests and demands for justice sweep across India. The brutality of this crime has understandably shaken the country’s conscience, thrusting the issue of sexual violence into the spotlight. However, while it’s necessary to condemn and react to such horrific cases, it’s equally important to widen our focus and confront the pervasive and often overlooked crisis of violence against women in India.

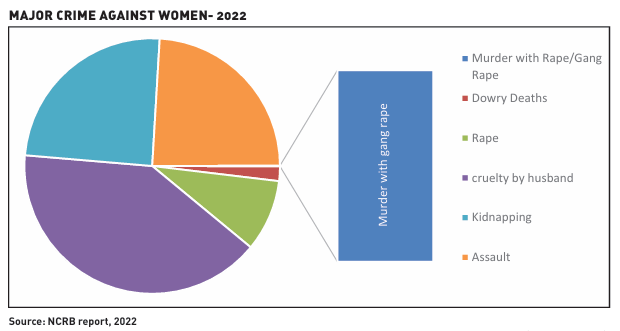

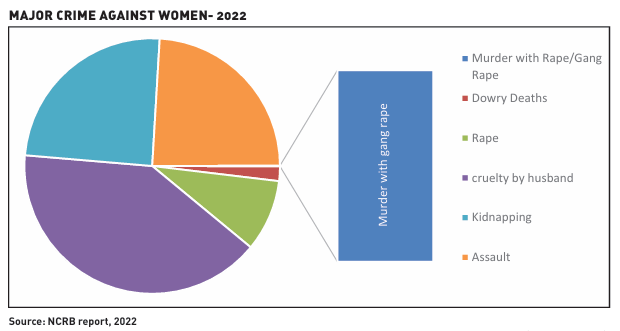

Rape, though one of the most heinous acts of violence, represents only a fraction of the abuse that women in India face daily. Women are subjected to various forms of violence—whether it’s domestic abuse, sexual harassment, molestation, and more. According to 2022 data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), cruelty by husbands/ relatives accounted for 140,019 reported cases, making it the most common crime against women. Sadly, even after more than 75 years of independence, in 2022, 6,450 women lost their lives to dowry-related violence, and 83,334 women reported assaults intended to outrage their modesty. Yet, there remains a deafening silence from both the public and policymakers regarding these forms of violence, as they often take place within the confines of the “private sphere.”

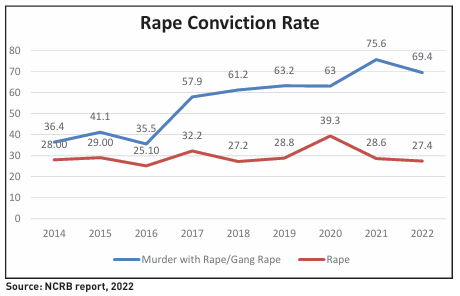

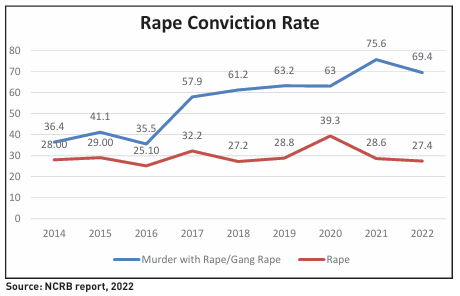

Rape weighs heavily on India’s conscience because chastity is upheld as a supreme virtue for women. However, not all rape cases evoke the same level of public outrage, and there is widespread societal ignorance regarding the large number of the rape incidents. NCRB categorises rape statistics under several headings, which can broadly be classified into rape and murder with rape/ gang rape. Of the 31,516 rape cases reported in 2022, only 248 involved murders with rape/ gang rape. Despite the severity of these cases, they account for just 0.01% of total reported rapes. Unfortunately, it is often these extreme cases that draw the most public attention and outcry. This bias extends into the justice system as well. While since 2014, conviction rates for murder with rape/ gang rape have nearly doubled, rising from 36.4% to 69.4% in 2022. In contrast, the conviction rate for other rape cases has slightly decreased, from 28.0% to 27.4% over the same period. These numbers reveal a concerning reality: while the most extreme cases are met with a strong legal response, the majority of victims are left waiting for justice, if they receive it at all.

It is worth asking why does the Indian society reserve its loudest outcry for cases of brutal rape and murder, while remaining largely silent on the many other forms of violence that plague women’s lives? Part of the answer lies in our collective discomfort with confronting the fact that violence against women is not an occasional horror, but a systemic issue ingrained in the fabric of our society. When we hear the word “rape,” it often brings to mind the image of a monstrous stranger, but this perception obscures the fact that the majority of the rapist often comes from within our homes, neighbourhoods, and social circles. In 2022, 97% of reported rapes were committed by individuals familiar to the victim but these cases are often shrouded in silence and rarely receive public attention, nor is there any societal pressure to ensure justice or support for the victims. These survivors seldom garner the same public sympathy or media coverage as high-profile cases. Instead, they are often left to endure a slow, biased, and retraumatising legal process, facing stigma and isolation from their communities.

In conclusion, the outcry in Kolkata is both necessary and justified, but it should be the beginning of a larger movement. A movement that doesn’t stop with seeking justice for one victim but aims to build a society where no woman has to live in fear—whether in public or within her own home. It’s high time the country addresses the deeper societal issues that allow such violence to persist. This demands a comprehensive approach: educating communities, reforming the legal system to be more responsive to all victims, empowering women to raise voice, and fostering a culture that condemns all forms of violence against women, regardless of the perpetrator. This effort should be accompanied by well-researched policy reforms that prioritise victim support and prevention rather than focusing solely on punishment. India will truly become a “Viksit Bharat” when every woman can live with dignity, free from violence, and has the opportunity to reach her full potential.

Jyoti Thakur is an associate fellow at NCAER, New Delhi. Views are personal.

Published in: The Daily Guardian , 03 Oct 2024